If you’re a musician, you are probably familiar with solfeggio (or solfege). But, if you are unfamiliar with the term or need a quick refresher course, please check out our full video on What is Solfeggio?

So, what do we mean by movable-do or fixed-do solfeggio? These are two distinct types of solfege and there are a number of variations on those styles as well.

With Fixed-do, C is always “do”, D is always “re”, E is always “mi” and so on through the scale. You don’t account for flats or sharps. So, it is basically note naming. The notes: C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C are called: do, re, mi fa so, la, ti, do.

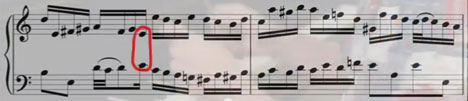

Movable-do is different from fixed-do except for the syllables. The notes in movable-do are based on pitch relationships so that “do” is the tonic of the major key you are in. So, in a piece with no sharps or flats, C is “do”. In a piece that has one sharp, G becomes “do” because you may be in G major. In a piece in G major (with F-sharp in the key signature) with movable-do, the notes: G, A, B, C, D, E, F#, G would be: do, re, mi fa so, la, ti, do! This is true for all keys. “Do” is the tonic (first note) of whatever key you are in. So, for example, if you had 5 flats in the key signature, D-flat would be “do”! You might wonder what the purpose of this is.

You also account for accidental syllables:

do – di – re – ri – mi – fa – fi – so – si – la – li – ti – do

Descending chromatic scale is:

do – ti – te – la – le – so – se – fa – mi – me – re – ra – do

Movable do can be extremely valuable for developing your ear. It enables you to hear all intervals since all scales have the same pitch relationships. For example, a perfect fifth will always be a perfect fifth whether it’s a C to a G, or a G to a D, or anywhere else. Utilizing movable-do can help you learn the pitch relationship between notes. It is a great tool for comprehending the music you hear.

Movable-Do

A great tool for hearing music

As a young child I was taught solfege and it is an extremely valuable skillset I utilize whenever I hear or play music. In fact, whenever I hear a piece of music, I automatically translate it into the syllables which helps me know the notes of music just from hearing it. It makes it possible to play by ear and to transcribe music I hear into written notation.

The problem with Atonal music

The whole idea of movable-do solfege is based on tonal music – having a tonic – that is having a starting note of the scale and all the pitch relationships between. Without this context, movable-do is meaningless and doesn’t work with atonal music.

Fixed-Do Solfege

Note naming is more important than you might think.

If you play the piano or the flute, it is probably not a big deal naming notes. Once you know how to read music, the notes are the notes and translating them to syllables may seem pointless.

But if you are a conductor, things are quite different. You have a many instruments in different keys and different clefs. It can be a great challenge knowing what notes you’re looking at. Note naming becomes an essential tool in this case for having a baseline for all the notes and naming them appropriately. It is also essential to communicate pitches with members of the orchestra.

Which One is Better?

This really depends on the situation and what your goal is.

If you want to be able to hear music and develop the ability to sight-sing music, transpose at sight, and transcribe music, learning movable-do solfege is an extremely valuable tool in achieving this. You will learn the relationship between notes to a very advanced degree that will make reading, transposing, and dictating music much easier.

Fixed-do solfege is a valuable tool in learning how to read a conductor score filled with various transpositions and a variety of clefs and being able to know what the absolute pitches are. If you’ve ever seen a conductor go through a score and digest it on the fly (realizing the music at the piano) it’s awe inspiring.

I hope this is helpful and if you have any questions about this topic or any other, please email me Robert@LivingPianos.com for more information.