I know this is a topic that might have some piano teachers in a panic at the suggestion of having students play their music too fast. Generally in performance and even in practice, playing your music too fast can be destructive. What I’m suggesting in this video is just one method of practicing your music – and something you would never use in a performance setting. It is a technique which used sparingly may provide insights into approaching your music.

You may have a piece you’ve learned and can’t get beyond a fundamental level of performance. I’ve found that sometimes playing a piece faster than written can open up new approaches and even new techniques you never thought to try. For example, if you’re playing a fast piece, playing it even faster will force you to lighten up your technique in order to accommodate the speed. Then when you come back to the normal tempo, you will find that you have more facility and comfort than before.

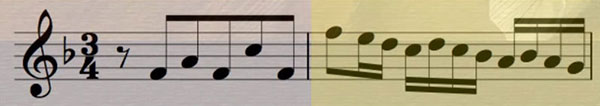

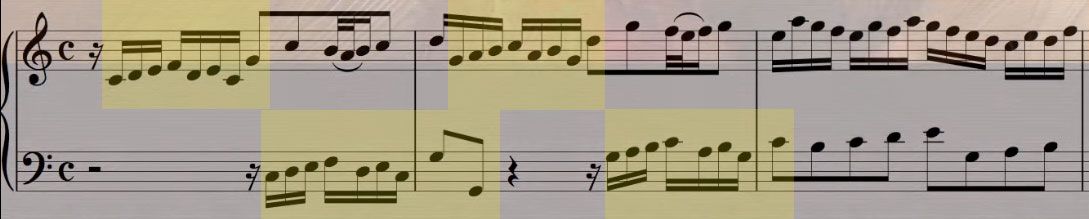

Even in slow movements this can be a beneficial technique. For example, in the Mozart K332 Sonata, the second movement is gorgeous and lyrical. Playing faster can provide insights into the direction of the musical line which you may not realize playing at the appropriate tempo. Sometimes you might find yourself getting bogged down and the music sounds choppy and lacking a fluid line. By practicing this movement faster than written, you’re almost guaranteed to approach it with a more fluid line. Try this and then go back to the written tempo and incorporate what you experienced playing at the faster tempo. You can sense the larger note values instead of each sixteenth note. You may be pleased with the results!

This is certainly not a technique I would recommend on a regular basis. However, it is something to try when you hit a wall with the progress of a new piece. I also have a video about the benefits of practicing your music slowly that is intrinsic to effective piano practice and something virtually all great pianists do on a regular basis.

Thanks again for joining us here at Living Pianos. If you have any questions about this topic or any others, please contact us at: Info@LivingPianos.com (949) 244-3729