Last time we discussed the differences between Fixed Do and Movable Do Solfeggio. Today we are going to go a little bit more in-depth and discuss how to handle minor keys in movable do solfege.

There are different schools of thought about how to approach the relative minor in solfeggio. We know that “Do” is always the tonic of any major key in movable Do solfege – so with no sharps or flats, C is “Do”, if you add one flat, F would be “Do”, and so on. But what about the minor? If you have no sharps or flats you could be in the relative minor of C major, which is A minor. So what syllables do you use then?

Some people will say that “Do” is always the tonic, so in the case of A minor, A would be called “Do”. I personally don’t like this approach and will explain why using “La” as the tonic of the minor makes perfect sense.

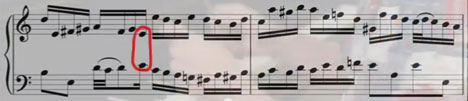

The great thing about using “La” as the tonic of the minor is that you don’t have to use accidental syllables where there are no accidentals found in the music. For example, if you were in A minor and there are no accidentals, if you started the tonic on “La” it would be: La, Ti, Do, Re, Mi, Fa, So, La. However, if you tried the same thing starting on “Do” it would be: Do, Re, Me, (accidental syllable), Fa, So, Le, (accidental syllable) Te, (accidental syllable) Do. This makes no sense; Having accidental syllables where none exists in the music is confusing.

Just think about dealing with pieces based on modes. The tonic can start on any of the tone degrees. Imagine figuring out all the modes starting on Do. This would be an arduous task! Instead, all the modes are simply like starting the major scale on different tone degrees. A dorian mode would be Re, Mi, Fa, So, La, Ti, Do, Re. So, all the modes are that simple to figure out!

Needless to say, I am a big proponent of starting the solfege on “La” when it comes to relative minor keys. It is particularly helpful in pieces that go back and forth between the major and relative minor. I would love to hear your opinions on this subject.

I hope this is helpful and if you have any questions about this topic or any other, please email me Robert@LivingPianos.com for more information.