I have been asked how to become a virtuoso musician many times and plan on doing a series on the subject. This is an introduction to the topic for you.

You probably assume that to become a virtuoso it will take hours and hours of practice of scales, arpeggios, repertoire, playing with other musicians, sight reading, and everything else that is involved in becoming an expert in your field; but there is more.

When it comes to the mechanics of playing an instrument and really mastering it, there is one similarity that all virtuoso musicians share. And this doesn’t just apply to musicians – it applies to any field from athletics to architecture, the absolute experts in their fields all share this similar quality.

At one point in their lives they immersed themselves so completely in their craft for an extended period of time that they developed a mastery that put them on a new level.

What does this entail for musicians? It means taking the time and effort to immerse themselves in their craft and even if they don’t always practice intensely every day for the rest of their lives, they have gone through a sustained period of time in their lives when they practiced nearly every available waking hour developing an extremely high degree of mastery of their instrument.

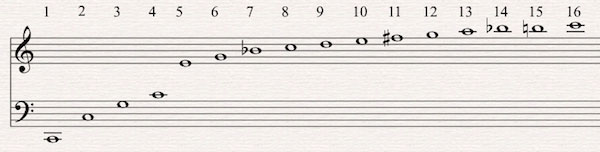

One parallel concept is what it takes to launch a craft into space. You need to travel a certain speed in order to break through the atmosphere and escape earth’s gravitational pull. If you continue to travel at a constant speed, you could travel forever but you would never escape earth’s atmosphere. You must hit a certain speed to break through that plane and get yourself out of the earth’s orbit. The same principle applies to become a virtuoso; at some point, you have to dedicate a significant amount of time in your life perfecting your craft and by the end of it you will have emerged as a different caliber of player.

It isn’t just a matter of how many years you practice, there also has to be an extended time in your life dedicated to absolute mastery of your field. I have spoken with countless virtuoso musicians, artists, and people in many different fields who have a great accomplishment, and they all have this exact same thing in common. If you have any similar stories I would love to share them.

Thanks again for joining me Robert Estrin Robert@LivingPianos.com (949) 244-3729.