Piano Lessons: How to approach polyrhythms

I have been asked to create piano technique videos for the great website: VirtualSheetMusic.com Here is one for you to enjoy. You may follow the link to watch others.

I have been asked to create piano technique videos for the great website: VirtualSheetMusic.com Here is one for you to enjoy. You may follow the link to watch others.

You’ve no doubt heard diminished 7th chords before. Anytime you hear spooky chords in an old horror movie or a Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody, works of Richard Wagner, as well as many other pieces of music, they are pervasive. They serve very important functions. But what are diminished 7th chords?

If you aren’t familiar with music theory or if you haven’t watched my past video: Explaining Musical Intervals – Whole Steps and Half Steps, I would suggest starting there. As a refresher, a half step is two keys together with no keys between and a whole step is two keys together with one key between. If this sounds confusing it would be a good idea to watch the video linked above.

A diminished 7th chord is built on minor thirds, so it’s one-half step bigger than a whole step (a step and a half, or 3 half-steps). Just as there is only one Chromatic scale and two Whole Tone scales, there are only three possible diminished 7th chords. After that, they are all just inversions – starting on different notes of the same chord.

When you build a diminished 7th chord you start with a note and count 3 half-steps to each successive note. After building 4 notes this way, if you build one more you will be back to your starting note! You will soon discover that unlike all other 7th chords, you can’t really invert a diminished 7th chord – it would still be a diminished 7th chord – all minor 3rds. So there are only three possible diminished 7th chords.

The great thing is that diminished 7th chords can go almost anywhere. They are incredibly useful in modulating to other keys and they can be used in improvisation as well. Next week we will be going much more in-depth with these chords and explaining practical uses for them.

Thanks again for joining me, Robert Estrin Robert@LivingPianos.com.

You’ve no doubt heard diminished 7th chords before. Anytime you hear spooky chords in an old horror movie or a Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody, works of Richard Wagner, as well as many other pieces of music, they are pervasive. They serve very important f

The piano is a unique instrument. I recall my third grade general music class. On occasion my teacher would let me play the piano for for everyone at the end of class and it was something I looked forward to. On one particular day when we were learning about the families of musical instruments, string, brass, woodwind and percussion, I asked if I could play at the end of class. But my teacher had a stipulation because of limited time. If I could tell her the classification of the piano she would let me play. I knew by the look on her face that it couldn’t have been something obvious which would be the string family, so guessed that the piano was a percussion instrument (the only other group of instruments I deemed possible). She was shocked that I had guessed correctly and she had to let me play!

So yes, the piano is a percussion instrument.

When the hammers strike the strings the notes sound and immediately begin fading away.

All music emulates the human voice to one degree or another. On wind instruments the connection is obvious – they utilize the breath. Even bowed string instruments produce continuity of sound not unlike the breath of the voice. So how do you emulate this quality on the piano, an instrument where the notes immediately begin to fade away as soon as you play them?

This is what we are going to discuss in detail today using the Chopin F# Nocturne (in the video example). I am going to provide a collection of techniques to help you achieve the tone you desire on the piano. Ultimately you are the judge of the sound you produce and you’ll use your ears to achieve the sound you want. These are guidelines to help you explore different tonal possibilities.

The first way to produce a singing line on the piano is to get louder towards the middle of the phrase and softer towards the end of the phrase. This is achieved not by calculating note to note but by using the weight of your arms to produce the desired tone. Here is an article and video which describes this technique in some detail:

The second way to produce a singing tone on the piano is to play louder as you play higher notes and softer when playing descending musical lines. The reason why this works so well is that when you’re singing or playing most wind instruments it’s natural for the higher notes to be louder than lower notes. This technique will create a different sense of phrasing from the method described above, yet the outcome is very lyrical.

The last method I’m going to share is something intrinsic to the piano. This is something that a master pianist Vladimir Horowitz utilized a great deal. Obviously you can’t completely replicate his style or methods which encompass many aspects, but you can attempt to create a similar tone production in your music. The method he utilized was to play longer notes with more energy than shorter notes.

Why does this technique make sense? It comes back to the physics of piano sound and the fact that as a percussion instrument notes are always fading away. For notes to last longer you must play them with more energy so they last long enough to create a musical line. If you try this on the piano it creates a singing quality in your music.

I hope these techniques have been helpful for you and as always you can send your questions, comments and suggestions to us directly: Info@LivingPianos.com (949) 244-3729

The piano is a unique instrument. I recall my third grade general music class. On occasion my teacher would let me play the piano for for everyone at the end of class and it was something I looked forward to. On one particular day when we were learni

One of the most common questions we get here at the store pertains to ivory keys and whether or not they are worth money. Since ivory is scarce today – and also illegal to buy/sell in many instances – it seems that they might be valuable on the second-hand market. This is not exactly the case.

First of all, when we talk about the white piano keys, we are referring to the keytops and not the keys themselves. Most of the piano keys are made out of wood and a cover of ivory or plastic is placed on top and in front of the keys. The pieces of ivory or plastic that go over the wooden keys are very thin. So, as a source of raw ivory, you are not working with much material when it comes to a single key top.

The biggest problem you are going to face is that selling ivory is illegal. Ripping the key tops off a piano and trying to sell them by themselves is not a good idea. For example, if you even try to list a product with ivory on eBay the listing will be removed – they simply don’t allow it. You also can’t transport ivory overseas and in some cases even in the United States, you may be prevented from selling ivory across state lines. So the market for selling ivory keys tops is very limited.

So what can you do with ivory keys you don’t need?

The best thing you can do is give them to your piano technician. Many times a technician will keep some ivory key tops with them in case one needs to be replaced on a piano. No two ivories are the same. However, there is a possibility they can match a key to an existing piano when a key top needs to be replaced if they have a big enough collection of old ivories of different sizes and hues.

Before the laws tightened, a set of ivory keys could have been worth thousands of dollars. There is some today who still sell them. You should use caution when dealing with ivory since the laws can be complex.

Thanks again for watching and please send any comments or suggestions to us directly: Info@LivingPianos.com

One of the most common questions we get here at the store pertains to ivory keys and whether or not they are worth money. Since ivory is scarce today – and also illegal to buy/sell in many instances – it seems that they might be valuable

Welcome to the first part in a multi-part series on chords. Today we are going to talk about how to identify the chords you are playing. I’ve had questions from people playing certain sonorities and wondering what exactly they are playing. In this lesson, we are going to talk about the basics of identifying chords.

The most basic thing to know about chords is that they are (almost always) built on the interval of a third. What is a third? A third is any notes that are on lines or spaces (not both) – they are two letter names apart. Here are some examples of thirds: A-C (leaving out B) or C-E (leaving out D).

Some chords are more sophisticated and they have what is called altered tones. This means that there might be an augmented or diminished chord that will have raised or lowered notes.

So knowing all this, how are you supposed to figure out what the chords are? It’s easier than you might think. Simply arrange the notes into thirds on the staff.

When you are reading your music, make sure that the notes are arranged in thirds. To do this, simply look at the notes that are on lines or spaces. Sometimes this can be tricky because there is something referred to as inversions. An inversion is done by taking the bottom note of a chord and placing it on the top (or the top note is placed on the bottom) – in the end, it will be exactly the same chord. So how do you know which chord it is? In an inversion, the notes will not be arranged in thirds, if you rearrange the notes until they form thirds (all lines or all spaces) you will find the root of the chord which is on the bottom. Take the bottom note and place it on top, or the top note on the bottom and the notes will arrange into thirds – all lines, or all spaces.

So how do you handle chords with more than three notes? The same principle applies to these chords. You can actually build chords all the way to the 13th utilizing only the interval of a third. Why is a 13 chord the limit? Because if you play one more third you will arrive back at the note you started on. This is because there are only seven possible notes within a scale and a 13 chord contains all of them!

This might sound confusing but once you start applying the basic principles in this lesson you will see that it makes perfect sense and is an easy way to identify chords. Next time we will be covering how to approach expanded chords.

Thanks again for joining us here at Living Pianos. If you have any comments or suggestions for future videos please contact us at: info@livingpianos.com (949) 244-3729

Welcome to the first part in a multi-part series on chords. Today we are going to talk about how to identify the chords you are playing. I’ve had questions from people playing certain sonorities and wondering what exactly they are playing. In this

The third part in my series on Hanon’s Virtuoso Pianist comes from a viewer question about how much to practice these lessons. In case you missed them here are the first two parts in my series on:

Part 2 – How to Practice Scales and Arpeggios

Believe it or not, there is such a thing as over-practicing exercises. One of the great things about the piano is that there is a wealth of music – so much so that it would be impossible to learn it all in a lifetime. So why practice strictly exercises when there is so much other music you could be learning and playing?

There are some instances in which you will need to correct technical problems with your playing and develop fluid a technique. Scales and arpeggios are a great resource for this. But how much is too much practice when it comes to exercises?

Generally, you should think of these as a warm-up to your practice session. If you dedicate 10 minutes to the beginning of your daily practice to focus on scales, arpeggios, or other exercises, it will benefit you immensely. What’s most important for your progress is the consistency of practice.

There may be times in your musical development when exercises can be critical in expanding your technique and developing strength. However, you should not ignore repertoire. You can continue to develop your strength and technical prowess while learning music as well – after all, we learn our instruments to play music!

Thanks again for joining me Robert Estrin: Robert@LivingPianos.com (949) 244-3729

The third part in my series on Hanon’s Virtuoso Pianist comes from a viewer question about how much to practice these lessons. In case you missed them here are the first two parts in my series on: Part 1 – The First Lessons Part 2 – How to Prac

We’ve had a lot of questions about this particular Mozart Sonata K 457 and today I’m going to address a very common question I receive about this piece. In the second movement, there is a section of very fast notes – some are 64th notes, some even go to 128th notes – and people are very interested in how to fit these notes in.

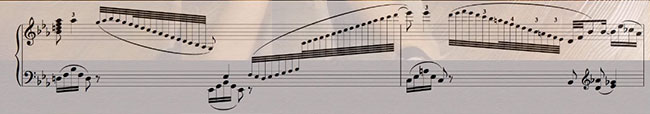

The simple answer is that you don’t need to fit these notes in perfectly as written – the final product should come out correctly but there is a certain level of freedom allowed. Here is an example of the section we are discussing:

That looks intimidating, doesn’t it? Well, there is a secret to playing this section and actually making it sound even better. Start the run a little bit early (just a hair before it’s supposed to actually start). Now is this going to affect the sound of the piece and make it lose its integrity? Not at all.

Mozart was known as a great improviser – as so many of the great composers of the past were – and they did their best to write down their music as accurately as they could. However, when it comes to cadenza-style passages, there is only so much you can do to write it down so that the music makes sense visually. So by experimenting with the timing, you can actually produce a better execution of the passage and not have to worry about having such a rapid string of notes. You are much better off not slowing down your tempo at all, but instead adjusting the timing to fit the notes in a musical way.

In the video example provided with this article, I show how I personally start a little bit before the run of notes. Would Mozart mind? I don’t believe so. I personally believe that you are always better off playing something that sounds good rather than forcing something. For example – How to Play Trills on the Piano.

You will want to play the number of notes you can execute comfortably and shouldn’t feel compelled to play a larger number of notes or strain yourself in playing higher notes in an attempt to keep the authenticity of the piece intact. Ultimately you must make music; that is the bottom line.

I hope this lesson has been helpful for you and I encourage you to experiment and play these pieces with your own interpretation and make them sound as great as you can. Thanks again for joining us, if you have any comments, suggestions or topic for future videos please contact us directly: info@LivingPianos.com (949) 244-3729

We’ve had a lot of questions about this particular Mozart Sonata K 457 and today I’m going to address a very common question I receive about this piece. In the second movement, there is a section of very fast notes – some are 64th notes, so

Today we are going to cover Double Sharps and Double Flats. You might think I made this up but it is an actual thing in music and it’s something that you should be aware of.

You’re probably familiar with sharps and flats and you might assume they are represented by the black keys on the piano. This, however, is not entirely true, sharps and flats are not just black keys on the piano.

Sharps and Flats simply raise or lower a note by a half step. A half step is represented by the closest interval. On a piano, this is a set of two keys next to each other with no keys between.

If you play C on a piano it is a white key. If you play a C sharp it is a black key. If you play a C flat it is a white key (the B key). The note that is sharp or flat is simply the next key to that note – whether it is white or black.

So what about double sharps and double flats?

Here is how you would see them in your musical scores:

So what does this mean and how do you interpret these notes. Well if a sharp or flat is simply a half step either higher or lower – then a double sharp or double flat is a whole step (or two half steps) higher or lower than the written note.

So let’s take the example of C again. If you had a C double flat, you would be playing the same key on the piano as B flat or A sharp. But why would someone write a double sharp or a double flat instead of just writing the simpler version of the note? This is because most Western music is organized diatonically – built on scales which have all the letter names in order – line to space, space to line. Sometimes it becomes necessary to use double sharps or double flats in order to notate the music logically adhering to the scale the piece is based upon. (for more information on this subject watch our video on E sharps and C flats).

I hope this was helpful for you and if you have any questions, comments, or suggestions for future videos please contact us directly: info@LivingPianos.com (949) 244-3729.

Today we are going to cover Double Sharps and Double Flats. You might think I made this up but it is an actual thing in music and it’s something that you should be aware of. You’re probably familiar with sharps and flats and you might assume they

Player systems have become incredibly advanced – many can be programmed using a tablet or phone. They can play historic performances of some of the greatest pianists of all time preserved digitally from the original expressive player piano roll