Welcome to LivingPianos.com, I’m Robert Estrin. The subject today is about the importance of reading music. Do you have to be able to read music to play the piano? Many of you know that I have a deep background in classical music. I am a second generation concert pianist. My father, Morton Estrin, taught me and my sister piano from a very young age. We were taught how to read notation, music theory, and all the rest of it. So you would think my answer would be yes, you must read music to play the piano. But I’m going to surprise many of you by telling you that, no, you do not have to read music in order to play the piano!

There are many pianists who can’t read music.

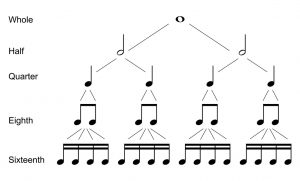

There are many accomplished players of country, folk, jazz, rock, blues, new age, and other styles, who can’t read music. Maybe they just read a lead sheet, which I’ll talk about in a moment. You’ll never be able to play the blues convincingly reading note for note. First of all, the rhythms are really hard to read with syncopated music like jazz, rock, blues, country and other styles like that. Secondly, the way that kind of music is created in the first place is with an improvised form. You are coming up with your own arrangements and playing by ear.

What about classical music?

I would never have wanted to believe this, but I have encountered quite a number of people who have become quite accomplished at playing sophisticated repertoire, learning note for note, following somebody else on the keyboard. They go on the Internet and watch videos of notes coming down on the keys like a video game. Does that really work? Well, it works to an extent. To get through a piece? Sure. Naturally, that technology doesn’t offer all the nuance of the notation, exactly how long notes last, the phrasing, how they’re connected and detached, and a myriad of other things. But talented musicians who don’t want to learn how to read music sometimes have good ears. They can watch the video, figure out where the hands go, and do a reasonably good job at recreating those pieces of music.

For anybody who wants to play classical music at a really high level, notation is a must.

For anyone looking to play classical music at a concert level, you will need to be able to read scores. But for those of you just wanting to play music and not be encumbered by the complexity of reading scores, particularly those of you who are interested in other styles of music, you can embrace it! I’ll go so far as to say that this is something that’s sadly neglected in conservatory training.

There are so many concert pianists who can’t improvise the simplest tunes by ear, because they’re never expected to.

As soon as they graduate, they discover that most of the gigs out there are not playing Beethoven sonatas and Chopin etudes. It’s really hard to find venues that are going to pay you to play that kind of music. So even if you are a classically trained musician, you owe it to yourself to explore improvised types of music. It’s good to be able to play music without necessarily reading it. A lead sheet is what most musicians utilize and most gigs expect you to be able to read. A lead sheet is just the melody line and the chord symbols. You come up with the arrangement. That’s the way so much music is created in this world! I’ll talk more about that in the future. Express your interest so I know how much of these videos you want to see! Thanks again for joining me, Robert Estrin here at LivingPianos.com, Your Online Piano Resource.

For premium videos and exclusive content, you can join my Living Pianos Patreon channel! www.Patreon.com/RobertEstrin

Contact me if you are interested in private lessons. I have many resources for you! Robert@LivingPianos.com